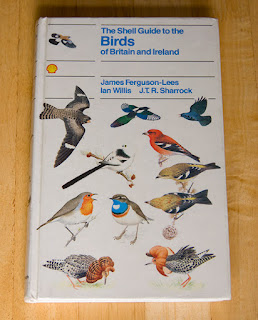

I was delighted to find a copy of the Shell Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland in a charity shop the other day. My original copy was thrown out years ago, so I was happy to pay a couple of quid for one in good condition, if only for the nostalgia.

I remember buying ‘the Shell Guide’, as it quickly came to be known, when it was first published in 1983, from WH Smith, or possibly one of the now long-gone independent bookshops in Leicester. I’d had other bird books before of course, but this was something different. Looking at it now, nearly 30 years later, the illustrations seem rather dated, and in many cases completely useless (some of the warblers and waders for example), but at the time the book was a revelation. Several different plumages were portrayed for each species (find me a modern book that shows 12 plumages for Long-tailed Duck!), with accurate captions (no vague ‘immatures’ here), up to date maps and population information, and detailed text.

I remember buying ‘the Shell Guide’, as it quickly came to be known, when it was first published in 1983, from WH Smith, or possibly one of the now long-gone independent bookshops in Leicester. I’d had other bird books before of course, but this was something different. Looking at it now, nearly 30 years later, the illustrations seem rather dated, and in many cases completely useless (some of the warblers and waders for example), but at the time the book was a revelation. Several different plumages were portrayed for each species (find me a modern book that shows 12 plumages for Long-tailed Duck!), with accurate captions (no vague ‘immatures’ here), up to date maps and population information, and detailed text.

But the best part for me, and I’m sure many others, was the fact that the book was split into two sections: ‘Regulars’ and ‘Vagrants’. And of course it was the vagrants section that captured the young birder’s imagination the most. Here were species I’d barely heard of, let alone thought ever occurred in Britain. And they were treated in almost as much detail as the Regulars.

One of the features of the Vagrants section was that the text gave the total number of records for each species at the time the book was written. Some of these seem incredible now as ranges have expanded, or more has become known about distribution or identification: Wilson’s Petrel, 8; Little Egret, 260; Pallid Harrier, 3; Ring-billed Gull, 37; Olive-backed Pipit, 18; Red-flanked Bluetail, 8, to give just a few examples. Of course, some species have stayed genuinely rare, and others such as Ortolan Bunting have declined to the point where they would almost be considered as vagrants rather than regulars now.

My first act on getting my original copy home in 1983 was to tick off the species I’d seen (it would have been about 150, with only one – Crane – in the Vagrants section), after which I set about trying to see as many of the rest as I could. I’ve often heard people talk about ‘finishing the regulars in the Shell Guide’. In common with many other people, I’m sure, my last one was Great Shearwater, 15 years after starting out on the quest to see them all. By that time my British list had grown from 150 or so to over 400, and my copy of the Shell Guide had been so used and abused that it literally fell apart.

I’m sure there were many other factors involved, such as the comparative lack of other distractions (no computers, no internet, just four TV channels etc), but I’m convinced the Shell Guide played a large part in inspiring birders of my age to get out there and see birds for themselves, whether by twitching rarities or just going birding. I’m surprised it’s never been updated – would a modern version with better illustrations be as inspiring I wonder, or would it just be lost amongst all the other bird books, magazines and websites constantly clamouring for our attention?